Micro-Frontends: From Monolith to Module Federation

JavaScript started quite timidly, modest and small. Its main purpose was adding interactivity to web pages. Back in the days, other technologies aimed for the same end: Java applets, VBScript and ActiveX.

In the Web 1.0 era, JavaScript relied on the engine designed by Brendan Eich in 1995 for the Netscape Browser, which evolved into SpiderMonkey—Firefox’s JavaScript engine still used today. But there was another ambitious project called V8, released by Google in 2008 as part of the Chromium project.

The V8 innovation led directly to the exaltation of JavaScript to the server side, allowing JavaScript execution outside a browser, with fully-fledged frameworks such as Express.js and more recent Next.js.

A Bit of History

As the Spanish philosopher George Santayana said: “Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it.” In order to grasp the current state of the art, we need to delve into its roots.

Web 1.0 refers to the original, information-oriented version of the World Wide Web. Created by Tim Berners-Lee in 1989/1990, it consisted of largely static webpages developed by a small number of authors for consumption by a large audience. — Michael Thomas, Handbook of Research on Web 2.0 and Second Language Learning (2008)

The following diagram illustrates the high-level functioning of the Web in its infancy:

The Web 1.0 paradigm couldn’t constitute a sustainable model. Users needed more—and the ability to share content. Web 2.0 emerged as the social web, where technologies from blogs and wikis through social networking sites to podcasting and virtual worlds became about communicative networking.

The barrier between classical heavy client applications and web applications shattered over time.

State of the Art: The Rise of SPAs

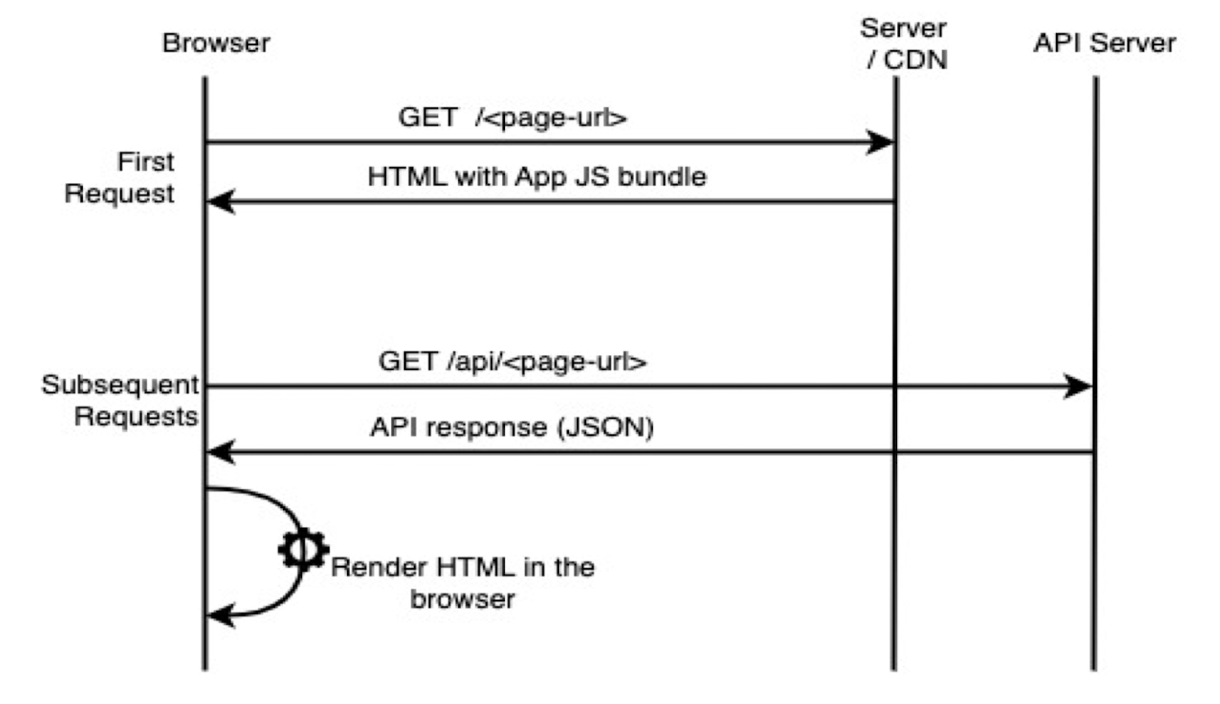

The shrinking barriers between heavy clients and web apps gave rise to a new hybrid approach, in which interaction with the user is performed by dynamically rewriting the application state with data from the server. This new paradigm signed the emancipation of Single Page Applications (SPAs).

“Better late than never” was the motto, giving rise to the frontend monolith with all of its “glory”, mimicking the backend modular model: modules, components, services, data binding, routing. A lot of frameworks loomed out of the dark age of spaghetti scripts: AngularJS, Ember.js, Knockout.js, Meteor.

The Problems with SPAs

Performance

Transposing the heavy client to the web comes at a cost: the initial loading time of all the JavaScript takes significant time, in conjunction with the processing cost of running both the browser and the JS engine threads. The extensive memory consumption and leaks compound the problem.

This might not be true for small to medium-sized apps, but it strongly holds for bigger, complex applications.

Complexity and Maintainability

As the holy SPA monolith grows in size, so does complexity and the cost of maintainability. The SPA’s “One ring to rule them all” maxim can only hold to a certain extent, for evolution is the essence of existence.

While a monolith still usually works out to be an efficient and productive solution—and many projects would benefit from the traditional paradigm—a modern approach lurks beyond its climax.

The Micro (R)evolution

After the frontend’s war for independence from backend hegemony and the establishment of the SPA’s republic, it was time to think outside the box.

The “Need for Speed” and efficiency requires further separation of concerns—this time at a higher level than conventional modularity and SOLID principles.

The success of the microservices architectural pattern heavily influenced frontend trends. What if individual segments of a web application could be developed and deployed independently, without compromising overall system availability?

Instead of building the frontend from a single codebase using a single framework, decomposing the application implies that each component is a standalone application with its own dependencies, build cycle, and deployment pipeline.

Implementation Approaches

iFrames

The simplest approach uses iFrames with message passing for communication:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>iFrames MFE</title>

</head>

<body>

<iframe src="./dashboard/index.html" id="dashboard"></iframe>

<iframe src="./orders/index.html" id="orders"></iframe>

<script src="app.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

// app.js - Cross-iframe communication

window.addEventListener(

"message",

(event) => {

document

.querySelectorAll("iframe")

.forEach(iframe => iframe.contentWindow.postMessage(event.data, "*"));

},

false

);

Webpack Module Federation

Module Federation allows loading remote modules at runtime:

// app-shell/webpack.config.js

const ModuleFederationPlugin = require("webpack/lib/container/ModuleFederationPlugin");

module.exports = {

plugins: [

new ModuleFederationPlugin({

name: "shell",

filename: "remoteEntry.js",

remotes: {

Nav: "Navigation@http://localhost:3001/remoteEntry.js",

Sidebar: "Sidebar@http://localhost:3002/remoteEntry.js",

Dashboard: "Dashboard@http://localhost:3003/remoteEntry.js"

},

shared: {

"react": { singleton: true },

"react-dom": { singleton: true },

"@mui/material": { singleton: true }

}

})

]

};

Podium (Server-Side Composition)

Podium uses Express.js to serve composable fragments called “podlets”:

// Podlet.js

import express from 'express';

import Podlet from '@podium/podlet';

const app = express();

const podlet = new Podlet({

name: 'myPodlet',

version: '1.0.0',

pathname: '/',

});

app.use(podlet.middleware());

app.get(podlet.content(), (req, res) => {

res.status(200).podiumSend(`

<div>This is the podlet's HTML content</div>

`);

});

app.listen(7100);

// Layout.js - Composing podlets

import Layout from '@podium/layout';

const layout = new Layout({ name: 'myLayout', pathname: '/' });

const podlet = layout.client.register({

name: 'myPodlet',

uri: 'http://localhost:7100/manifest.json',

});

app.get('/', async (req, res) => {

const content = await podlet.fetch();

res.send(`<html><body>${content}</body></html>`);

});

Common Concerns

Each approach addresses the same set of concerns differently:

- Scripting scopes: How JavaScript executes in isolation

- Assets and styles: CSS isolation (Shadow DOM, CSS-in-JS, namespacing)

- Routing: Navigation between micro-frontends

- Inter-MFE communication: Sharing state and events

In contrast to microservices, micro-frontends bring increased complexity:

- Payload size (multiple framework instances)

- Governance complexity

- Performance and security

- Team productivity and organization

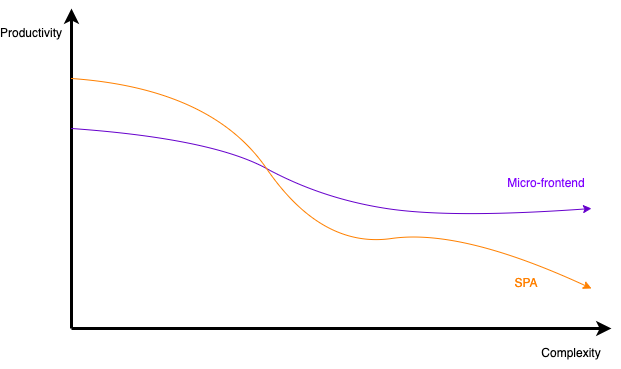

The following graph illustrates the relationship between complexity and team productivity when using either SPAs or micro-frontends:

Architectural Patterns

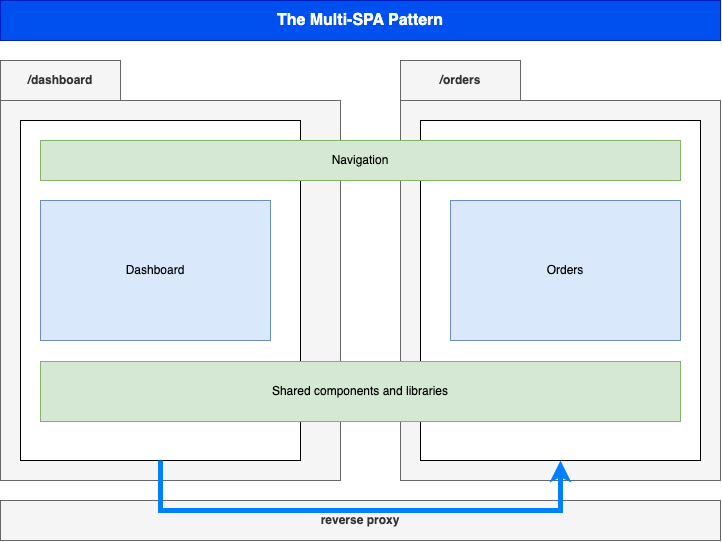

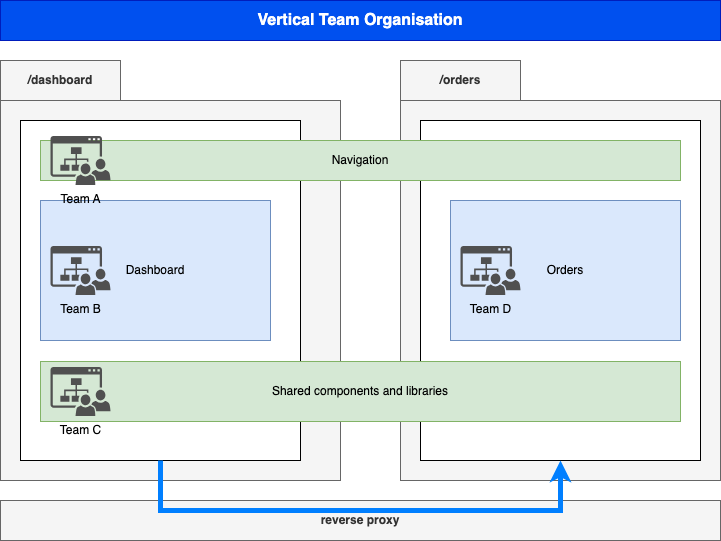

The Multi-SPA Pattern

Think of micro-frontends as a swarm of SPAs linking to each other, with shared components and libraries. A reverse proxy simulates the behavior of a traditional monolith.

This is the simplest approach for teams embracing the paradigm—two independent SPAs respond to their respective routes while sharing navigation components and UI libraries.

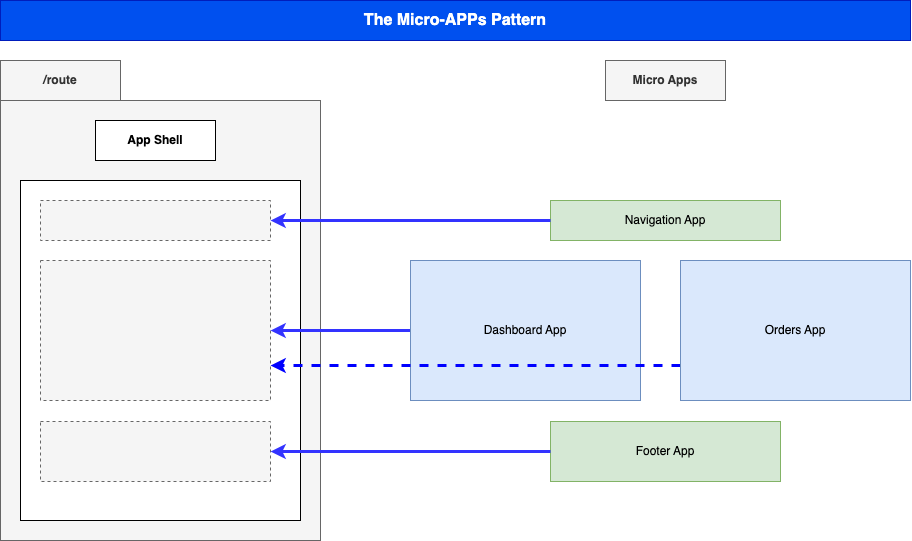

The Micro-Apps Pattern

More “micro” than Multi-SPA: each component is a truly independent application developed, built, and deployed separately.

An App Shell loads first and handles loading other components, routing, and lifecycle. Central security and state management systems live within the shell.

Each micro-app runs on its own infrastructure, allowing:

- Selective composition in response to user interaction

- Technology independence

- Failure isolation

- Flexibility

The orders team can modify, build, and deploy their components without impacting the whole system. The application runs fine even if the orders component is rebooting or failing.

Composition Strategies

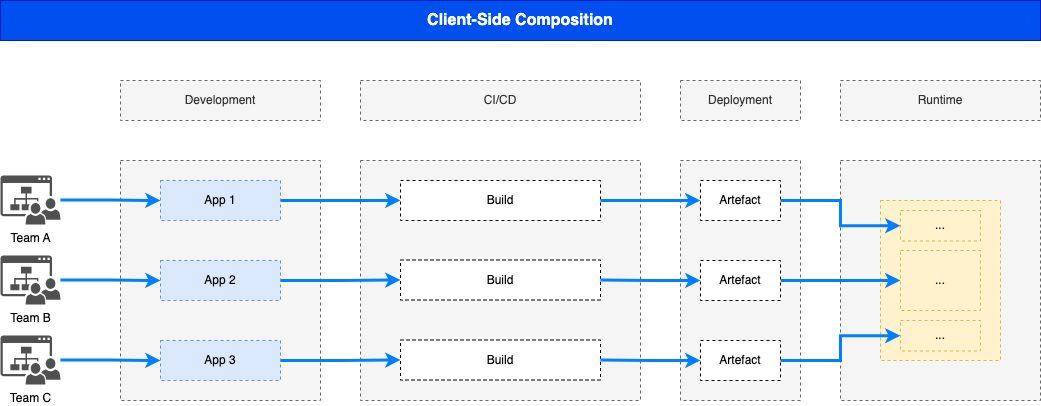

Client-Side Composition

Lazy-loads components from a parsed App Shell. Webpack’s Module Federation leads this approach.

Pros: Truly independent and isolated Cons: Performance concerns when using different frameworks—response time and bundle size grow

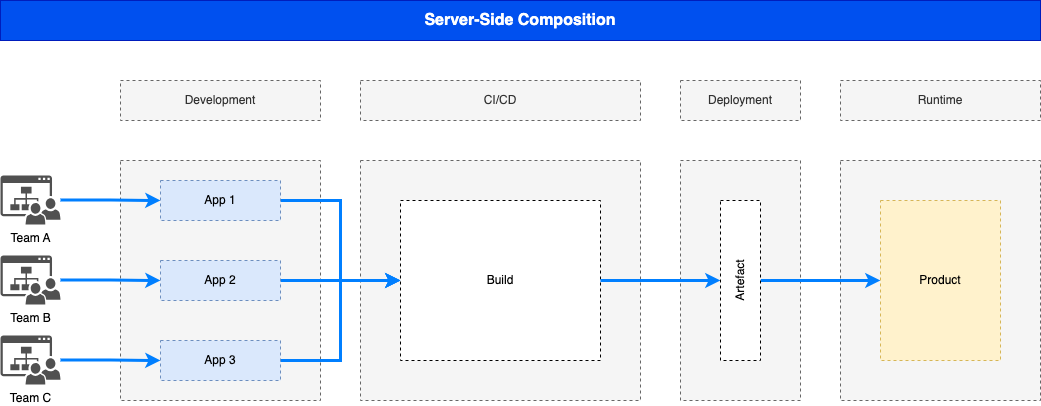

Server-Side Composition

Restrains performance loss by composing on the server. Podium is a promising framework for this approach.

Pros: Optimized loading time on the client Cons: Requires server-side architecture—scalability, reliability, and availability implications

Team Organization

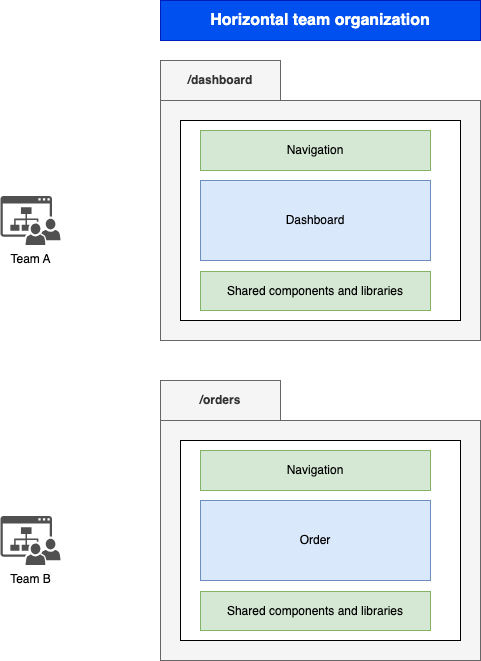

Horizontal Teams

Each team is responsible for a single domain while contributing to shared components and libraries. Teams focus on features across the application.

Vertical Teams

Each team focuses energy on a single component, enforcing domain decomposition, team independence, and technology independence. Aligns well with Domain-Driven Design principles.

Benefits of Micro-Frontends

When the philosophy is properly adopted and technical aspects adequately implemented:

- Scalability: Independent scaling of components

- Failure isolation: One component’s failure doesn’t bring down the system

- Independent development: Separate builds and deployments

- Promotes DDD: Automation and DevOps culture

Challenges and Cautions

Exercise utmost vigilance when dealing with micro-frontends:

- Complexity cost: Implementing, deploying, and managing distributed frontends

- Performance and security: XSS, CSRF vulnerabilities across boundaries

- Code duplication: Especially in Multi-SPA patterns

- Cross-team coordination: Communication overhead

Conclusion

Micro-frontends represent the next evolution in frontend architecture—applying the lessons learned from microservices to the browser. But unlike backend services running in isolated containers, everything in micro-frontends runs on the same browser instance, making the technical constraints more demanding.

The key insight: micro-frontends solve organizational problems as much as technical ones. They enable teams to work independently, deploy frequently, and own their domains end-to-end. But they come with complexity costs that only make sense at sufficient scale.

Choose wisely. For most projects, a well-structured monolith remains the efficient choice. Reserve micro-frontends for when the organizational benefits outweigh the technical complexity.

Micro-Frontends: From Monolith to Module Federation

A comprehensive study on the evolution of frontend architecture.

Achraf SOLTANI — June 15, 2024